I came across this insightful review of Saffron Dreams from 2010 which I feel is pertinent to read in today’s political climate.

I came across this insightful review of Saffron Dreams from 2010 which I feel is pertinent to read in today’s political climate.

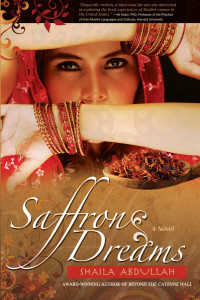

Shaila Abdullah’s Saffron Dreams Reviewed by Deborah Hall, Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies Vol. 2, No. 3 (2010)

Shaila Abdullah’s novel, Saffron Dreams, chronicles the journey of Arissa from Pakistan to America, from widow to recovered woman, from traumatized daughter then traumatized wife to a professional editor and single-mother devoted to her special-needs child. Her husband’s death in the World Trade Center on 9/11 is the critical event around which the plot of this novel pivots, but in the end, Saffron Dreams is a novel of hope from which we learn from Arissa how to deal gracefully and patiently with life’s cruel turns.

Abdullah isn’t so much offering an analysis of the misguided guilt-by-association to which Arissa is subject as she is capturing a human story that happens to be about a Pakistani Muslim couple. There is one scene shortly after 9/11 in which Arissa is a victim of physical violence from a racist group of young men who follow her off the subway, harassing her and cutting her clothing. Once they realize she is pregnant, they run off.

In another scene, the hostility is less violent but shows cultural ostracizing. When a 9/11 missing persons flyer of an Arab man catches Arissa’s eye because he looks like her missing husband Faizan, she stops, mesmerized until she realizes a white man is staring with hostility at her:

“This one is mine,” I pointed to the flyer of the young man…“Which one’s yours?”

He stared at me in disbelief. “None,” he said finally.

I turned to leave.

“I am sorry,” I heard him say but I could not stop and answer. (87)

In this circumstance, one might understand how religious defensiveness grows into religious shame or how one might assimilate into the dominant culture as a survival strategy. In fact, the novel opens with an act that appears as a cultural (or religious) rejection of the veil. Arissa is walking to the Hudson River late at night. It’s been two months since 9/11. It seems like she’s going to throw herself into the dark water. Instead, she “grasped the cold railing with one hand and swatted at the fleeting [veil] with the other as the wind picked up speed…[she] let it sail down toward the depths,” (3). She muses about how this ritualistic unveiling might look like betrayal to a Muslim onlooker, but concludes she is merely shifting the veil “from her head to her heart” (3), but the larger, cultural explanation is that she is making herself less of a target in Muslim-phobic, post-9/11 America.

The characters in Saffron Dreams defy simplicity, but more importantly they defy Muslim stereotypes. One example is Arissa’s mother who has a love affair and abandons her family. Arissa’s siblings suffer through the absence of their mother, marry, give birth and move on with their lives. The mother returns to their lives through long-distance phone calls that Arissa will not accept. After missing Arissa’s marriage and failing to come to Arissa’s side during the 9/11 crisis, Arissa is not moved by her mother’s plea to resolve their differences. At the end of the novel, Arissa has the strength to absolve her mother of all obligations toward her. In an act that is horrifying to the mother, Arissa says there is no chance of a relationship. When the mother yells, “You can’t discard me like day-old trash,” (223) the irony is obvious.

In Arissa, Abdullah captures a female character who has escaped the typical confinements of her culture, using tradition when it benefits. Her mother is narcissistic. Her father is a liberal, educated physician who wants his children to be happy. For her younger sister’s happiness, Arissa and her father consent to the younger sister’s marriage before Arissa, the eldest female. While Arissa’s mother behaves in a way that cripples her children and severs the mother-daughter bond, Arissa becomes an example of self-determination when she uses the village match-maker to her benefit to match her with Faizan and an example of maternal devotion as she raises a special-needs baby as a single mother.

Once Arissa has moved to America with Faizan, a Columbia University graduate student studying literature, she grapples with defining herself within her marriage. Once her husband dies, she must struggle with overcoming her grief, living independently, becoming a good mother, nurturing her creativity and talent (finishing her husband’s novel as a tribute to him) and finding her womanhood again. The novel follows this journey from Arissa’s abandonment by her mother to her becoming a self-sufficient, artistic, sexually-mature, and maternal woman.

The novel’s unassuming and poetic style is more introspective than dramatically-rendered thanks to Abdullah’s artistic instinct which focuses more on the inner landscape of her characters than the tragic terrorist attack. At times, Abdullah’s dramatic scenes are both poignant and intimate. In this scene Arissa’s father tells his children, “Your mother has left.” Abdullah captures this scene impressively:

The unnerving words echoed across the dining room and like a leech drained the surroundings of all air. The ear-piercing silence that followed became an incessant buzzing that wouldn’t go away. Like a bone, the joke we were laughing at minutes earlier got caught in our throats. Zoha’s hand, which had just lifted a spoon to bring it to her mouth, came to halt midair, and I saw her lower lip tremble. It could only mean one thing. I curled my fingers over her arm and gently but firmly guided the spoon into her mouth. She began to chew her cornflakes slowly as tears ran down her cheeks. Sian, 14 at the time, laid his spoon on the table on the side of his plate, wiped his face clean with a napkin, and escaped to his room without a word. (23)

Abdullah’s writing often captures the sights and smells of her native Pakistan with poetic lyricism. Describing the wedding of Arissa and Faizan, she writes that the separate stages in the wedding hall were “decked with red and orange batik covers and a flowery curtain of moghra (jasmine) and genda (marigold) flowers, a mingling of the milk and saffron of our lives, joining the ordinary with the extraordinary, a tantalizing fusion of mind and senses,” (40). Often during this novel, the smells and tastes are as rich as the colors of the “tie-and-dye print dupatta” used to cover the bride (39).

Arissa’s character at the end of this novel symbolizes a maturity and evolution that exemplifies one who has endured not one but many tragedies. While doting on her son Raian, she ponders how she might tell him about her native Pakistan: “I might…tell him that when you leave a land behind, you don’t shift loyalties— you just expand your heart and fit two lands in. You love them equally,” (174). The same might be said for a woman who must love again after having loved and lost. Saffron Dreams is an important American novel. The Pakistani-American immigrant story has not seared enough the consciousness of the American psyche. Americans often think that 9/11 was a singular American tragedy. Saffron Dreams reminds us that 9/11 hurt Muslims in more devastating ways because it stole their innocence and reputation. It allowed, as Abdullah says, “a lynching of a religion,” (155). This novel reminds us that Islam is based on “tolerance, peace and bridge-building” (120) and the great many non-extremist Muslims around the world (dull, un-dramatic and ordinary as they are) get to define who they are and in what they believe.

As much as I’ve focused on 9/11 in this review, it doesn’t equal the measure of attention Abdullah gives the subject in her novel. She focuses much less. To be sure, Saffron Dreams is a love story; moreover, it’s a woman’s journey, and if I strayed from that focus it is because tragedy steals the show. But Abdullah’s instinct resists this very thing. The beauty of Saffron Dreams is that it celebrates common acts of humanity and reminds us that while loyalty and devotion might go unnoticed, they are examples of daily heroism. For that lesson, I’m grateful for having read this novel.